The New York Times is an independent journalism company that is dedicated to helping people understand the world. Through a series of videos, interviews, photographs, and opinion columns the New York Times presents “the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of party, sect, or interests involved”. Although the New York Times covers a wide breadth of news, such as politics, health, and travel, my focus lies within the arts column. The article I will review within this bracket is titled “Félix Fénéon, the Collector-Anarchist Who Was Seurat’s First Champion”.

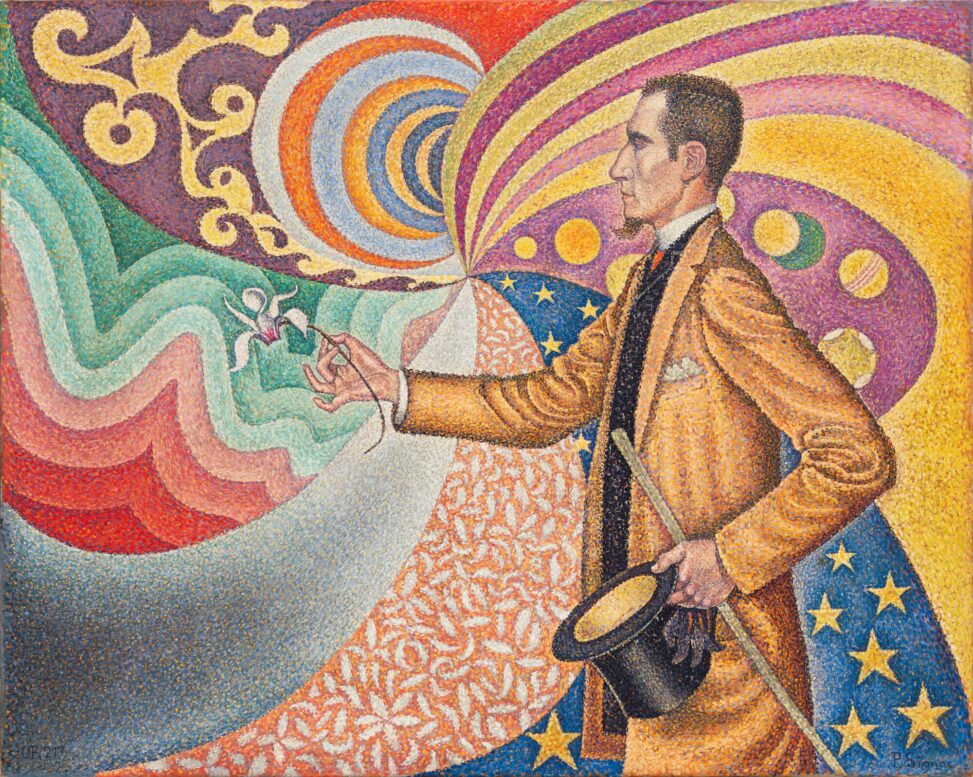

Written by Roberta Smith, the co-chief art critic of The New York Times, she provides a thorough and refreshing take on the exhibit Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond. Though never an artist himself, Fénéon was a “confirmed dandy” whose lasting achievement is reflected in the materiality of his extensive collection and current exhibition.

To briefly summarize her article, Smith begins by introducing the creators of the show. Born from a collaboration between Isabelle Cahn, chief curator at the Musée d’Orsay, Philippe Peltier, a former department head at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, and Starr Figura, curator of prints and drawings, the exhibition currently resides in the Museum of Modern Art. She then goes on to explore Fénéon’s childhood history and describes his later years as an anarchist and art collector. In the second half of her critique, Smith describes the layout and objects in Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond as well as Fénéon’s relationships with the artists whose work he possesses and elaborates on his time as an anarchist.

Just as the exhibition “exudes a certain warmth of feeling”, I felt that Smith’s article did as well. By walking through the works on display and describing their origins and impact, such as Henri-Edmond Cross’s “The Golden Isles”, Edouard Vuillard’s “The Folding Nude”, and posters designed by Toulouse-Lautrec, she effectively frames the exhibition. in a way that is thorough, yet comprehensive for viewers who may not be familiar with Félix Fénéon and his life’s work. Even an outsider who is unfamiliar with the art sector would not feel intimidated in reading her critique as she offers enough background information to contextualize the objects she discusses. While it can serve as an introductory guide, it can appeal to well-versed audiences as well, though more as a recap tool rather than a basin of new knowledge. While there is no age requirement or restriction, the article seems to align itself with readers who are interested in Félix Fénéon’s exhibit and his lasting impact on the Neo-Impressionist movement, regardless of their level of expertise.

Although her article is classified as an art critique, I felt that Smith was fairly neutral when describing the MoMA’s exhibition. While she does include phrases such as “an amazing show” and “stunning groups”, her goal is not to persuade the reader whether it was a well or poorly executed exhibition, but rather inform them of the exhibition’s presence and layout. Smith provides just enough context for those unfamiliar with Fénéon’s work, and in doing so, does not insert her own opinions. For instance, when writing that Fénéon “was the discoverer of Georges Seurat , and coined the term Neo-Impressionism”, she does not state if this was a good or bad recognition, but simply a discovery. While some, such as myself, might be tempted to praise Fénéon for discovering the creator of pointillism, Smith simply provides facts without imposing her own judgement.

Although the New York Times is often labeled as a liberal news source, I felt that this did not influence the article as Smith’s review was fairly neutral and did not discuss politics. For me, I enjoy reviews such as these because it encourages viewers to attend the exhibition and enables them to develop their own viewpoints of what is presented in front of them. Viewers do not approach this exhibition with preconceived judgments created by critics, but rather their own personal background, beliefs, and experiences.

As Smith acknowledges in her critique, rarely do museums initiate exhibitions that spotlight non-artists. However, the MoMA went where other museums could not and developed an exhibition that highlights Félix Fénéon, a prominent critic, journalist, gallerist, and art collector during the turn of the 20th century. in the art world. Through this exhibition, we are offered a glimpse of the other side of the art dialogue (in reference to Holly Shen’s question, the “non-art-making side) and provided context, through Smith’s article, to Fénéon’s scholarship and the artists he worked with during the turn of the 20th century. In writing this article, Smith emphasizes the importance of recognizing individuals such as Félix Fénéon, in the art world because they are the ones that “make things happen”.