In her article “Portrait of An Artist Not to Be Underestimated”, Howardena Pindell examines her 1990 mixed-media work “Scapegoat”. Here, Pindell contextualizes its creation, explaining how this installment is part of her “Autobiography” series and a reflection of her personal experiences.

Analyzing Pindell’s work through an art historical lens, I immediately drew a connection between “Scapegoat” and Lukasa (memory board), a mnemonic device of the Luba peoples. The Metropolitan Museum of Art describes Lukasa as “handheld … objects that present a conceptual map of fundamental aspects of Luba culture”. Often made of wood and inlaid with shells and beads, Lukasa are used as memory devices to assist the reader in recounting Luba history. However, a unique aspect of Luba culture is that their history “is not chronological and static as Westerners learn it [but] rather … a dynamic oral narrative” (Moss).

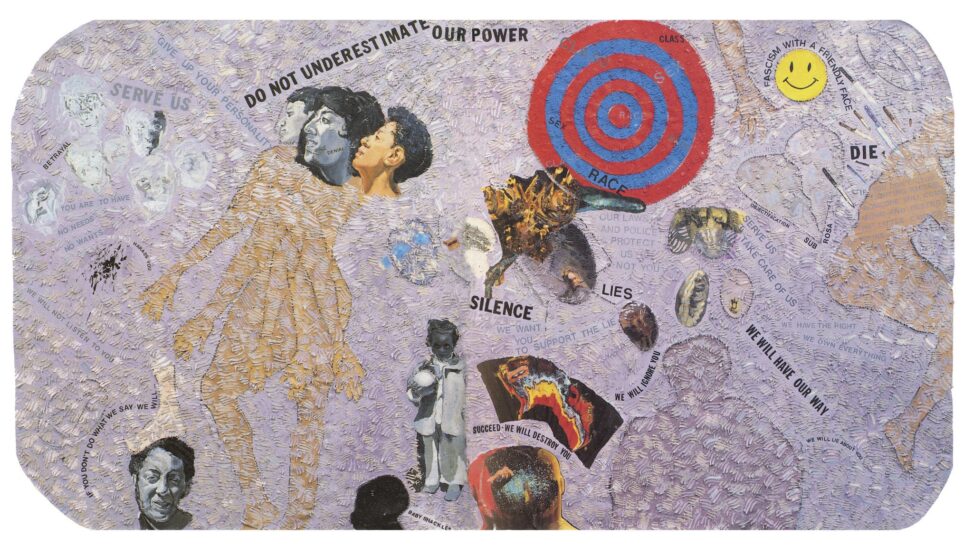

In “Scapegoat”, we are learning the history of Pindell’s life in a way that is similar to the Luba people. Though not in a performative sense, we are visually presented with a snapshot of Pindell’s life through an unsequential approach. Specifically, “Scapegoat” contains four portraits of Pinell, all at various stages in her life; “one with the foot of [her] ex-boss at the Modern stepping on [her] head” while another features Pinell as a young girl holding a ball (Pinell). In the top right is a target that deals with issues of racism (Pinell). Pinell leaves the remaining imagery of “Scapegoat” for viewers to analyze and interpret themselves. The portraits and symbols are not in chronological order and there is no lineage in which the images are conceived. However, this does not hinder our perception or understanding of the work, but rather enhances it. The focus of both the Lukasa and “Scapegoat” is not sequential order, but rather the information that is being shared.

While the Luba peoples’ retelling of the past is dynamic in a physical sense (it is performed through song and dance), Pindell’s work, on a conceptual level, explores dynamic themes, including racism, sexism, and xenophobia. Racism, sexism, and xenophobia are dynamic in the sense that they passed through successive generations and take on different forms.

Just as the Luba peoples use their history to “interpret and judge contemporary situations”, we also see images of Pinell’s past experiences echo larger contemporary issues being addressed in her work (Moss). Although Pinell does not provide specific examples of the oppression she has endured, there are several symbols (the target and smiley face) and phrases (“DIE”, “SERVE US”, “FASCISM WITH A FRIENDLY FACE”) that allude to her abysmal experiences. These were most likely not single occurrences. However, she also includes phrases such as “DO NOT UNDERESTIMATE OUR POWER” and “WE WILL NOT LISTEN TO YOU” that represent the moments she spoke out against her oppressors and reclaimed herself. “Scapegoat” itself is a testament to Pindell’s resilience.

Though created in different contexts and composed of varying mediums, I was instantly drawn to Lukasa when viewing Pinell’s work due to their powerful ability to preserve memory. Ultimately, Pinell’s “Scapegoat” and Lukasa of the Luba peoples are works that capture experiences of the past while acting as social tools that not only reaffirm their creator’s existence but also transform it into collective memory.

Sources

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/690570?rpp=30&pg=1&ft=lukasa&pos=

Juliet Moss, “Lukasa (Memory Board) (Luba peoples),” in Smarthistory, November 28, 2015, accessed September 2, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/lukasa-memory-board-luba-peoples/.